01.07.2015.

Nataša Kandić: Serbia is politically and socially responsible for Srebrenica

There is responsibility for that genocide, there is criminal responsibility, but there is also political and social responsibility. In the context of the political and social responsibility, one must prohibit not only denial of the genocide but also insulting the human dignity of the victims. Any polemic as to whether it was a genocide, whether it was the most serious of crimes, makes no sense, because there is the criminal judgement of the International Court of Justice. What is more, the years in the wake of that crime must be dedicated to respect, and to expressing sympathy for the victims, and not on any account to political polemics and the stimulation of a negative climate. The polemics as to what Serbian national interests are, what is conducive to reconciliation and what is not, and the interpretations that resolutions which pay respect to the victims are not in the spirit of reconciliation – all that is impermissible, especially in the context of the twentieth anniversary of Srebrenica. It is the duty of all to create a benign climate, where the priority should be sympathy for the victims of the Srebrenica genocide.

Interview with Nataša Kandić

Interviewed by Amer Tikveša and Senad Haskić

On the occasion of the twentieth anniversary of the Srebrenica genocide, we have interviewed Nataša Kandić, the great human rights defender, Coordinator of the RECOM project and former Executive Director of the Humanitarian Law Center (HLC) in Belgrade.

The twentieth anniversary of the Srebrenica genocide is upon us; does Srebrenica in your view symbolize a genocide of modern times?

Srebrenica is the symbol of the most serious and most massive suffering since the Second World War in Europe. There is, of course, Rwanda too; but what happened in 1995 was something that people believed could never take place in Europe, the Balkans included. There were, however, indications that something like this could happen in the Balkans in the aftermath of the Second World War. When the former Yugoslavia began to fall apart, there were a number of indications that grave crimes of this kind were being contemplated. We should not forget that in May 1992, at the Assembly of the Serb People in Banja Luka when Ratko Mladić was put in charge of the Army of Republika Srpska and the Assembly proclaimed the separation of the peoples as its objective, it was Mladić himself who first used, there and then, the term ‘genocide’, in connection with the proclaimed goal of the Serb Assembly. He said on that occasion that this proclaimed goal, the separation of the peoples, could not possibly be achieved in such a way that the Serbs would remain alone; he said that he did not know how Krajišnik and Karadžić would explain this to the world; and he said, ‘Folks, that’s genocide’.

Today Ratko Mladić is being tried for genocide. And it was he who said in May 1992 that the goal proclaimed by the Assembly as a national interest was essentially a genocide. In this regard, nothing was done from 1992 to 1995 to prevent that genocide from taking place. And that’s how the genocide came to be. There is responsibility for that genocide, there is criminal responsibility, but there is also political and social responsibility. In the context of the political and social responsibility, one must prohibit not only denial of the genocide but also insulting the human dignity of the victims. Any polemic as to whether it was a genocide, whether it was the most serious of crimes, makes no sense, because there is the criminal judgement of the International Court of Justice. What is more, the years in the wake of that crime must be dedicated to respect, and to expressing sympathy for the victims, and not on any account to political polemics and the stimulation of a negative climate. The polemics as to what Serbian national interests are, what is conducive to reconciliation and what is not, and the interpretations that resolutions which pay respect to the victims are not in the spirit of reconciliation – all that is impermissible, especially in the context of the twentieth anniversary of Srebrenica. It is the duty of all to create a benign climate, where the priority should be sympathy for the victims of the Srebrenica genocide.

You have already visited Srebrenica. How do you personally feel when you attend the commemoration of those events, given that both victims and VIPs are among those present? How does it feel being there on the anniversary in the midst of such striking contrasts, with some wishing to be seen, others in mourning? What are your personal feelings when you are out there?

Ever since the Documentation Centre in Potočari was opened, it has seemed to me that it is increasingly taking on a very concrete meaning: it is going to be a place where one learns about what happened as well as where one pays one’s respects. I believe that in time it will become a place to which secondary school pupils and students will come, above all to listen to witnesses and to hear evidence. When you visit that cemetery in order to pay respects to all those victims, you feel differently if you have first familiarized yourself with the details and become fully informed. What is important in my view is that there are a great many incidents connected with Potočari, and also all over the region. We don’t all of us have to be there on the day of the burials; what matters is that we should make public protests at various locations with the object of mobilizing all the citizens, the entire population from the region of the former Yugoslavia, to pay their respects to the victims. Incidentally, I am especially moved by that girl’s song, which is repeated every year. Everything else is changing…The people, the mothers, the sisters are changing, all of them are getting older, some of them are gone and cannot come to visit the graves; but that song, that girl’s voice reminds us year after year that the grief remains and that we must keep the dead in mind all the time, that we must do nothing that might cause them further harm. We must also bear in mind that the years are passing and that it will be left to future generations to organize the paying of respects once the families are no longer there. This is why it is important for the content to be infinitely variable but that the song should be kept for ever, to remind us always in the same way – everything else is going to change with time. I believe that there is going to be more tenderness, more sympathy, more respect; however, I would personally like that song to be heard on each anniversary.

What is your explanation for Serbia’s non-recognition of the genocide?

Serbia relies on the judgement of the International Court of Justice, and says that Serbia is not responsible for the genocide. This means that it took no part in the commission of the genocide but is responsible for the failure to prevent it – this is Serbia’s trump card in not using the term genocide. That a crime was committed in Srebrenica has been established in criminal judgements and in the judgements of the International Court of Justice. Therefore, any country aspiring to restore the rule of law must not deny that a genocide took place and must not disregard the decisions of a criminal court such as the Hague Tribunal and a court of justice such as the International Court.

Vučić has also said that he is concerned about the situation in Bosnia and Herzegovina and that he is fearful of new developments over here; however, there are no references to Serbia. To what extent does that policy affect these porous relations within Bosnia and Herzegovina?

I think that everything that happened in connection with the commemoration of Srebrenica has set back relations considerably. However, I think that everybody must take care of the climate in their own country and consider how much they can contribute to regional stability. But no one must take charge of relations in another state, because the states created on the territory of the former Yugoslavia are fully independent in the conduct of their policies. What the presidents and the prime ministers should have in common is a constant concern to minimize the extremisms. The aim should be to identify in time the possible negative consequences of those extremisms, to minimize them and to join forces in order to prevent a spillover of terrorism, a strengthening of the right and a repetition of the situation that existed on the eve of 1990.

In other words, we need politicians who are absolutely willing to curb the strengthening of the extremisms of their own nationalisms, and to work towards the establishment of the rule of law through war crimes trials, with the help of a regional commission which would register all the victims, create a name register of all the victims and put an end to the manipulation we’ve been witness to since the Second World War. The aim should be to find out how many persons were killed where, who were then thrown into various pits and lime-kilns. We must know the names of the people who were killed because of their names

Serbia is professedly on the road to the EU, and Bosnia is professedly on that road too. Do these two countries have, in principle, a common peaceful future?

I am encouraged that everything, after all, is moving in a better direction. [I am encouraged] that communication is regarded as being the most important of all, that there is no longer that fear that the people felt, that, if you look around, you see a lot going on, a great deal of exchange, a great deal of combined activity, and that there is no longer room for fear. I firmly believe that there are a good many of us now and that, if we weren’t able to do it back in 1991, we who have no weapons can now stop those who have them, that we can do that now, thanks to all the experience we now have. I hope that there are both politicians and others who would never allow us to find ourselves in a position where we could have that happen to us. Mind you, we must be aware of what happened – the deaths, the killings, the dispossession, the destruction of homes -, and that those things happened to ordinary people. We can count on our fingers the politicians who experienced any of this; those who were prepared to fight till the last minute to preserve some peace were the ones who were made to suffer. On the other hand, those who found their interests in the war, in weapons, in the new sources of enrichment, they keep silent now. However, I believe that there are sufficient guarantees, sufficient energy, sufficient strength, to make sure there is never a repetition of the 1990s preparations for the war that started in 1992.

You have had problems because of what you do. This has also often been mentioned in the media. What is the situation in this regard today – are you still having problems and how do you deal with that?

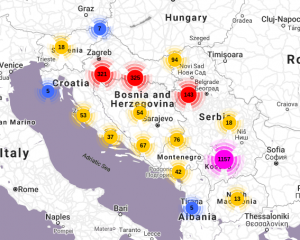

You know, if you are concerned with human rights, you take things like that in your stride. I’ve come to accept that what I do is not to the liking now of this group, now of that group, and not to the liking of the politicians. Although the politicians have never liked what I do, I took it as something to be expected; there is no other way where war crimes and gross violations of human rights are concerned. I have reached an age where I can’t help thinking about how important it is that every victim should be known by his or her name, and that there should never be a repetition of Jasenovac. Today we still talk about the numbers of people killed without knowing the names of those people. This is why we advocate the establishment of a regional commission which would compile a register of all the victims. Needless to say, however, we must know the circumstances and the fate of those civilians, we must know how the soldiers lost their lives, and whether they were killed in action; some of them also lost their lives as victims of war crimes – they were executed following their detention. Then there’s the question of what happened in the camps – one must create a register of all the camps and places of detention. This is something to which I am now very much committed. Also, I hope that the politicians will accept help from the civil society, which is currently working on identifying the victims by name, to set up a regional commission in order to remedy the deficiencies of the courts, whose remit does not include registering victims by name. The duty of the courts is to establish the responsibility of those who have been indicted. This is very important, and I think that trials should be kept up. Here in our region, one is apt to hear people say, ‘‘There, that man’s a criminal and he walks around freely.’’ I think the courts should have to determine whether that is true, whether there is a criminal at large. If he is free, why is no one filing a criminal complaint, why is nobody arresting him? However, what is important is to use the capacity of the civil society to drum up as much respect for the victims as possible. This is why I think that what I am doing, and what, for instance, the Association for Transitional Justice, Accountability and Remembrance in Bosnia and Herzegovina and the Centre for Democracy and Transitional Justice in Banja Luka are doing, is very important as a strong impetus to the states to set up jointly a regional commission to make sure the facts are established, that no crime is forgotten, that each name is known and that the foundations are laid for building a culture of compassion for the victims.

(Published na portalu GlobalX, 29 June 2015)