13.01.2016.

Political Theatre in the Region: a Small Contribution to History

Communication has got underway,

let us wish it well

Author: Sonja Ćirić

Although it is impossible to prove it with exactitude, cultural exchange is certainly the good spirit that has the power to break down boundaries and bring together what has been separated, because it provides an opportunity for people to meet and bond with one another. Especially people who are or have been fighting against one another. When it comes to theater and its influence on the change in relations between the former Yugoslav republics who were at war with each other during the 1990s, this thesis has proven to be true.

The first play from Belgrade to be performed in a former Yugoslav republic was Oleanna, produced by the Atelje 212 Theater. It happened on 5 May 1995, in Maribor, Slovenia, while the wars in Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina were still in full swing. Oleanna, a drama written by David Mamet, was translated into Serbian and directed by Vida Ognjenović. Svetozar Cvetković and Nataša Čuljković played the two characters in the drama. However, the press was totally silent about this guest performance at Maribor’s Slovensko narodno gledališče (SNG).

“It is no accident that it was not reported in the press, as we played it incognito” Svetozar Cvetković said for RECOM.link. “Serbia was under sanctions at the time and we wanted to show that things here were not as people there thought they were. We took a train to Vienna, via Budapest, and planned to travel from Vienna to Maribor by car. However, at the Hungarian-Serbian border, Serbian customs officers entered our compartment and asked us to get off the train because they had information from Maribor that our performance had been cancelled. It so happened that while we were travelling to Maribor, Zagreb was being shelled from Karlovac, where Ratko Mladic’s troops were located. The Croatian National Theatre (HNK) was hit – its ballet rehearsal hall, and two people were injured. It was an outrage, and they thought that the Serbs had deliberately shelled the HNK. The Slovenian Ministry of Foreign Affairs responded by banning from its territory all plays coming from the aggressor country. We were in constant touch with Tomaž Pandur, director of the SNG. Our initial idea was to continue to Vienna, and Tomaž would transport our audience to Vienna by buses so we could play Oleanna, which was a chamber play, for the roughly one hundred people who had bought the tickets. Then another idea occurred to us: the Maribor Theatre should announce that the performance had been cancelled, and keep the theatre building unlit, and we would nevertheless go there, let the audience into the unlit theatre and perform the play incognito. And that is exactly what happened. Hence the absence of press reports.”

Restoring regional ties

Nearly three years after Oleanna, on 7 and 8 of May 1998, Powder Keg, written by Dejan Dukovski and directed by Slobodan Unkovski for the Yugoslav Drama Theatre (JDP) from Belgrade, was performed in Ljubljana. The Belgrade daily newspaper Naša Borba, in its article “Actors applaud the audience”,underlined that the first Yugoslav “expedition” to Slovenia did not have to detour through Hungary to get to Slovenia, but travelled directly through Croatia. The text goes on to say that “several actors from Zagreb came to see their Belgrade counterparts, including Mustafa Nadarević, and Radko Polič and Davor ‘Autsajder’ (Outsider) Janjić from Ljubljana were also in the audience”, adding that both performances were sold out. “Local theatre connoisseurs were surprised by the artistry displayed by a young generation of actors whom they had not had a chance to see at work.” The performances took place at Cankarjev Dom, “a leading Slovenian cultural institution which had hosted political events that in the not-so-distant past had cast a burden on Slovenian-Serbian relations, because of which the symbolic character of the performances were even more pronounced.” The Ljubljana daily newspaper Delo saw the guest performances of the JDP as “a true breath of fresh air in the Slovene theatrical landscape”. Elaborating on this, the author stated: “First and foremost, because after several years (to be precise, nine years, as the last play from Serbia that had been performed in Slovenia before Powder Keg was Calling the Birds, in 1989 – author’s remark), we had an opportunity to see this important theatre, the spirit of which used to ennoble the Slovene scene in the past, and which, as has been shown, we have indeed missed.”

These events marked the beginning of a renewal of cultural cooperation between once hostile countries in the region. Back in those “early” days, the very crossing of the borders – irrespective of the theme and content of the plays – was a political statement in itself.

In December 1997, Kamerni teatar 55 from Sarajevo performed Strindberg’s Miss Julia, directed by Faruk Lončarević, on the stage of the Atelje 212 Theatre. This encounter was organized by the Swiss Embassies in Belgrade and Sarajevo, with, as reported by Naša borba, “the generous assistance of the Ministry of Culture of the Republic of Serbia”. The text further states that “the quality of the performance, understandably enough, was of secondary importance”, and the symbolic importance of this guest performance exceeded by far its achievement on the stage. Dragan Marinković, an actor in the play, said on that occasion that the guest performance had nothing to do with politics nor did the ensemble want it to. “Some people thought we should not have come to Belgrade before they came to Sarajevo. I understand this point, but I wonder which of those people stopped playing their shows when the wars in Slovenia and then in Croatia broke out. None of the Sarajevo theatres closed, as far as I remember – I never read that any theatre had closed, in solidarity with our colleagues in Slovenia and Croatia. For all of them it was happening somewhere very far away.”

In January next year, Atelje 212 reciprocated by performing Art in Sarajevo and Mostar, and thus become the first Belgrade theatre to have guest performances in post-war Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH). Art, written by Jasmina Reza, was directed by Alisa Stojanović and played by Svetozar Cvetković, Branislav Zeremski and Tihomir Stanić. It was performed twice in Sarajevo and twice in Mostar.

At a debate organized by the Coalition for RECOM in Belgrade on 13 December 2012 about the next steps towards reconciliation in the region, Dino Mustafić, a theatre director from BiH, recollected the guest performance of Atelje 212 in BiH: “What an irony. It was the first post-war guest performance, Art. Atelje 212 obtained the text by Jasmina Reza through the Swiss Embassy. Next to the Eternal Flame in Sarajevo, near Tito Street, two tanks were guarding the artists from Atelje 212 who performed in Sarajevo. Few theatre-makers from Sarajevo went to see the play, because we somehow ignored it. I was vehemently against it, because I did not see it as a genuine guest performance of Atelje 212, but as something that came as a result of the political dictate of the international community.”

Atelje 212 was the first theatre from Serbia “to break the ice after nearly a decade” and perform in Croatia, as Belgrade daily newspaper Politika reported on 18 October 2000. 75 members of Atelje 212 ensemble went to Croatia to perform at the Ivan pl. Zajc Croatian National Theatre in Rijeka, as part of the European Millennium Festival. They performed Biljana Srbljanović’s Family Tales, directed by Jagoš Marković, and Ronald Harwood’s Taking Sides, directed by Lenka Udovički. Both shows were sold out.

The Belgrade press headlines highlighted that “the cultural exchanges should have never been interrupted”. Novi List from Rijeka dedicated a whole page to the guests from Belgrade. Its theatre critic wrote: “Family Tales concerns not only Serbia but ourselves too. Everything we have seen taking place on the stage is like an image in the mirror, because everything the play speaks about is something that we in Croatia can very easily relate to. Maybe the problem is that we haven’t often got to hear similar bitter stories and crushing truths about ourselves on the Croatian stage”.

The local press was most interested in Ljuba Tadić, the actor who portrayed the prominent German conductor Wilhelm Furtwängler in Taking Sides. Answering some political question in an interview for Novi list, this doyen of the former Yugoslav theatre scene – as Tadić was introduced by the newspaper – said that he was not into politics, that he was an actor. But added: “I have been an artist who believed that art is detached from politics, but I nevertheless knew that art is politically manipulated, that is inevitable. So I lie to myself a bit when I say I am not into politics – I am a public figure and I react to certain current events, and that is politics. I take sides. This guest performance will also be manipulated, if need be.”

Rade Šerbedžija, the husband of Lenka Udovički, director of the play, was also in the audience. He shared his impressions of the performance with the Belgrade daily newspaper Blic’s correspondent: “A very special kind of celebration took place in Rijeka this evening. And hail not only to this great play and the fantastic performances delivered by Ljuba Tadić, Pera Božović, Petar Kralj and other actors. There was extra applause in support of the new life that should begin to develop in the region. That was the message of the audience in Rijeka, which, of course, made me very happy.”

Painful Encounters

Aside from the abovementioned guest performances, there were other regional theatre exchanges in all directions at the same period. But the most important one that drew most attention were the reciprocal guest performances of the national theatres in Sarajevo and Belgrade, which took place in 2001.

For the Belgrade National Theatre, this was their very first guest performance in the region. On 19 May, its ballet ensemble performed three short ballet pieces on the stage of the Sarajevo National Theatre, namely: Béla Bartók’s The Miraculous Mandarin, choreographed and directed by Dimitrije Parlić, re-staged by Duška Sifnios; De Falla’s Amor Brujo choreographed by Lidija Pilipenko; and Cage, Lidija Pilipenko’s ballet piece to the music of Gustav Mahler. Two weeks earlier, the Sarajevo National Theatre Ballet performed two pieces choreographed by Edina Papo – the Pulcinella Suite to the music of Stravinsky, and Apple, to the music of Britten, Verdi and Rachmaninoff,

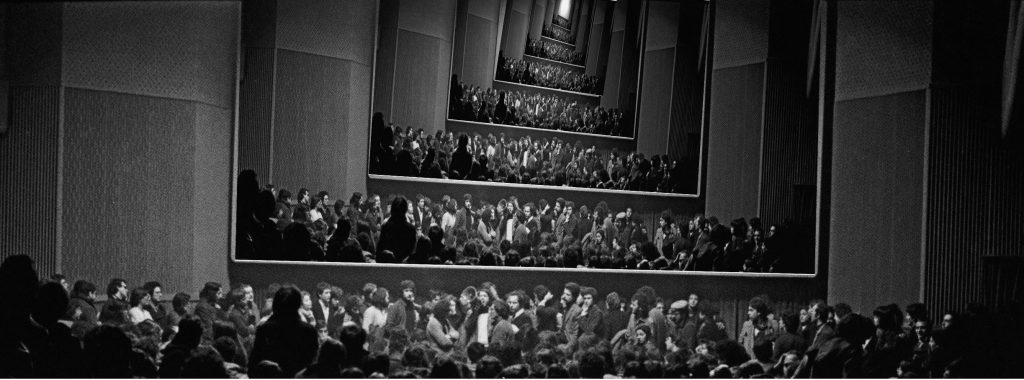

“The performance in Belgrade was historic for both theatres”, said Edina Papo on that occasion for Belgrade’s Glas javnosti. The Belgrade weekly NIN published a story about the reception of Caroline Neuber, by Nebojša Romčević, performed at Sarajevo’s “Kamerni teatar 55”. “The atmosphere is solemn, the theatre is packed. A complete success! The Sarajevo audience is beguiled, their palms are tingling from the clapping that lasts forever. They are whooping with delight and shouting ‘Come visit us again!’ It was wonderful to be from Belgrade that evening in Sarajevo”, wrote Slobodan Joković for NIN. Since 2001, guest performances have been organized on a regular basis.

Judging by their statements, regional cooperation meant a lot to its participants and audiences alike. However, it did not result in the opening up of painful questions dealing with the past and responsibility. The cooperation consisted primarily of exchanging goodwill gestures with a healing effect, without touching the wounds from the past, but allowing them to heal at least a little.

There were just a few texts dealing with the war that had just ended and its consequences. One of them, Biljana Srbljanović’s drama The Fall, which, according to Ivan Medenica, “substantively and symbolically represented political theater at its highest in the Serbian theatre of the nineties”, premiered at Belgrade’s Bitef-teatar in 2000, just days before the actual political fall of Slobodan Milošević. In her play Rails, Milena Marković used short, pungent lines to articulate the different emotional states of a generation whose youth unfolded amid the war and horrors of the nineties. The play was staged at the Yugoslav Drama Theatre in 2002 by the Macedonian theatre director Slobodan Unkovski. Ear, Throat, Knife, a monodrama, based on the novel of the same name by the Croatian author Vedrana Rudan, adapted for the stage and performed by Jelisaveta Sablić, and directed by Tanja Mandić Rigonat for Atelje 212, spoke trenchantly of a number of subjects that do not appeal to everyone. It ran from 2003 to 2007 and was also shown in several cities in Croatia and Slovenia. The novel by Vedrana Rudan was subsequently dramatized and staged in Croatia as well, first at the Teatar 101, and subsequently at the Rugantino Theatre. It was performed by Gordana Gadžić. A long article published in Hrvatska riječ on the occasion of its guest performance in Subotica reads, among other things, as follows: “This play gives us food for thought, incites us to try to accept those who are different, and thus brings us onto a path towards a more meaningful communication with ourselves and therefore with those around us. The communication has got underway, let us wish it well.”

On 14 March 2008, the Council of Ministers of Culture of South East Europe met in Zagreb to adopt the Declaration on Cultural Cooperation in the Region, which reaffirms their commitment to enhancing intercultural dialogue and cultural cooperation with the aim of contributing to the peace and prosperity of South East Europe. That document formalized the cooperation that had already been well underway. An example of such cooperation was the competition for the best contemporary drama in the Serbian or Bosnian language, organized jointly by the Sarajevo MESS Festival and the Belgrade Drama Theatre. The first winner was Ćeif , by Mirza Fehimović. As stipulated in the cooperation agreement, Ćeif was produced by the Belgrade Drama Theatre in 2007 (directed by Egon Savin) and premiered at the MESS Festival. It is one of the most awarded plays produced in Serbia, and it is still running. Following its opening at the MESS Festival, Dino Mustafić, Director of the Festival, said that Ćeif opened “a new dimension of our relations”, as in it Serbian actors speak about the Bosnian reality.

The last ten years or so have seen quite a few regional theatre projects. Such projects are highly desirable, both because of the need for exchange of knowledge and skills, and because of the need to pool resources. For example, one of the most popular and successful projects of the Yugoslav Drama Theatre (until the death of actor Đuza Stojiljković) was Elijah’s Chair, based on a text by the Croatian writer Igor Štiks (an interview with this writer is published alongside this text – author’s note) and directed by Boris Liješević. It was staged in 2010, as a co-production of the Belgrade’s JDP and the Sarajevo MESS Festival. The Belgrade Drama Theatre and the Zagreb-based Kerempuh Satirical Theatre have signed a protocol that envisages the exchange of performances and joint projects. All four plays shown last year at the Budva Grad-Teatar Festival in Montenegro, were the fruit of cooperation of several theatres from the regional centres. The list of theatrical projects that resulted from regional cooperation is a long one, and regional cooperation is no longer an exception.

But the question remains: why did theatres in the region articulated post-war social problems and a critical reflection of these problems only at the end of the first decade of this century, and why they still have a long way to go when it comes to dealing with these topics? Striving towards this important goal, Borut Šeparović and Oliver Frljić in Croatia problematize some of the most sensitive topics in that country. Borut Šeparović, for example, explores the effects of the war legacy and conservative upbringing on young people in his Generation 91-95. In Mauzer, he deals with crimes against Serbs during operation “Oluja” (Storm) and the case of General Ante Gotovina. Oliver Frljić in Spring Wakening speaks of the damaging influence of the Catholic Church on the younger generation.

Such powerful political theatre is what the region lacks most. In this respect, probably the smallest progress has been made by Serbian theatres. It was only when the Croatian director Oliver Frljić staged Cowardice at the National Theatre in Subotica in 2011 that the Serbian audience was made to face up to Srebrenica. In this play, the actors read out the names of more than 500 Srebrenica victims killed by Serbs.

The heritage of Yugoslavia as a theme

At the beginning of the second decade of this century, theatres in the region became interested in the legacy of Yugoslavia, and this became a frequently explored theme. Plays and playwrights explored whether the Yugoslav legacy is merely an object of memory or a valid contemporary identity construct, whether our attitude towards it boils down to (Yugo)nostalgia, or whether we can look at it with a critical eye. In dealing with this topic, several plays have raised some painful issues of the past – issues that had been hushed up and not spoken about. Born in YU, produced by the Yugoslav Drama Theatre (written by a group of authors led by Božo Koprivica and directed by Dino Mustafić), and Hypermnesia, co-produced by Heartefact Fund and the Bitef teatar (dramaturge Filip Vujošević, director Selma Spahić) epitomize this approach. Both plays are based on the personal experiences of the actors and have a documentary quality. Ivan Medenica, in a text for the Teatron magazine issue dedicated to this topic, wrote: “The very title Born in YU suggests not only the documentary character of the play but also the attitude towards the material the play is based upon. Not only do the personal memories of the actors make up the basic material of the play, but the play shows no ambition to process that material into something more than intimate, individual experiences of what being Yugoslav means to a group of randomly assembled actors, nor does it take a critical stance towards it.” Hypermnesia had a multiethnic cast of characters, which also suggests the political character of the play. For example, in a scene where a Serb girl and an Albanian young man are simultaneously giving their accounts about the first days of the 1999 bombardment of Serbia, we see two conflicting truths about the same event. The same approach was used in the scene in which three actors who come from three different cities – Sarajevo, Pristina and Belgrade – simultaneously recollect what they were doing on 28 June 1989, when Slobodan Milošević delivered a speech at the Gazimestan rally, the speech that was a harbinger of the collapse of Yugoslavia. The actors speak in their native languages, without translations. This was probably the first time in years that the Albanian language was spoken on a Belgrade stage. Hypermnesia powerfully touched on what is probably the major taboo topic in Serbia, that of abuses against Kosovo Albanians by Milošević’s regime.

And then in May 2012 Atelje 212 staged Zoran Đinđić, a project by Oliver Frljić. According to Branislav Trifunović, an actor in the play, the aim of this play was to “not let people forget and to make them start thinking for themselves. The play neither glorifies nor belittles Serbia’s assassinated late Prime Minister, it just tells a story about a country”. Since Golubnjača, no play has caused so much controversy as Zoran Đinđić. It would be futile now to list all the reasons for this, many of which were irrational, but let us mention just a few: the play was considered by some to be more a political pamphlet than a stage play; others were annoyed by the scene in which an actress throws up on the Serbian national flag, others by the fact that the Serbian Orthodox Church was portrayed as a warmonger, and others that the play declared the people responsible for the Prime Minister’s assassination….

It could be said that the entire cycle of Oliver Frljić’s productions contains elements of explicit critique of state policy. In his latest project, The Ristić Complex, shown during the 2015 BITEF Festival, an actor urinates on a Serbian map, which is a reference to the plays by Ljubiša Ristić, perhaps the most important theatre director in the former Yugoslavia, whose works Frljić has used as a starting point for his play. The Ristić Complex was just one of the five plays shown at the 2015 BITEF Festival that could be classified as political, i.e. engaged theatre. Their themes and artistic approaches differed. The one that stood out among them was Ibsen’s An Enemy of the People as a Brecht’s Teaching-Play, a project by Zlatko Paković (co-produced by the Belgrade-based Centre for Cultural Decontamination and The Ibsen Scholarships, Norway) is a good example of highly political theatre. It brings together the legacies of two of the greatest figures of the modern political theatre, Ibsen and Brecht, and introduces them into the context of the present-day Serbia. More specifically, Paković puts on the stage Tomislav Nikolić being interviewed by a well-known TV journalist, shows victims of transition, people who belonged to the middle class during the socialist Yugoslavia. The aim of this project is, in the spirit of Brecht, to show the audience how to recognize a hidden truth in society and to inspire them to fight for their own freedom – because we are nothing without freedom.

Another Paković project, Encyclopedia of the Living, is also a good example of political theatre. The position that “we should share the responsibility for our community” uttered at the beginning of the play, is consistently elaborated and proven throughout the play, by reminding the audience of Serbia’s attitude towards Kosovo, and vice-versa, from the (unresolved) 1985 incident concerning a bottle that was taken out of the anus of Đorđe Martinović, which became “the driving force of the territorial poetics of the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts”, to last year’s “secret supper” organized in Tito’s former hunting lodge in Dedinje, and attended by Aleksandar Vučić, Ivica Dačić, Hashim Thaqi, Edita Tahiri and Momčilo Bajagić Bajaga. The events and characters portrayed are called by their real names, in Serbian and Albanian. The message the play conveys is that national and nationalist elites are dealing out the hashish of nationalism to the poor, so that poor Serbs and poor Albanians exterminate each other, while their elites draw profit from their mutual extermination and consolidate their power.

Encyclopaedia of the Living is an artistic intervention into Serbian and Kosovo realities, produced by the Belgrade Centre for Cultural Decontamination and Qendra Multimedia from Pristina. It opened in November in both Belgrade and Pristina, and was shown in Novi Sad too. The authors of Encyclopaedia of the Living are: Zlatko Paković (writer and director) and Yeton Neziray (writer), Borka Pavićević and Shkelzen Maliqi (dramaturgs), Božidar Obradinović (author of music) Gjergj Prevazi (choreography), Krste Džidrov (scenography), Marija Pupučevska (costumes), and Adrian Morina, Shengil Ismaili, Shpetim Selmani, Igor Filipović, Faris Berisha and Zlatko Paković (cast).

Kosovo was also the theme of Romeo and Juliet, directed by Predrag Miki Manojlović. It is a co-production of Belgrade’s Radionica integracije and Qendra Multimedia from Pristina, featuring actors from Belgrade and Pristina who play in Serbian and Albanian, without translations. The press carried Manojlović’s statement that the play “pursues a common creative aim” to warn us, as he put it, that “if there is no coexistence, this part of the world may as well call it quits and turn off the lights.” The play ran only last spring, with four performances at the Belgrade National Theatre and four at the Pristina National Theatre. The audiences in both cities applauded. Some critics praised the idea of a bilingual performance (all characters with the Capulets spoke Serbian and those with the Montagues spoke Albanian). The excellence of the actors also won praise, as did the scenography, shaped in the form of the letter “X”, which hid the unspoken answer to the question of the reconciliation of the warring sides in the play. The press also carried the statement by Yeton Neziray, playwright and director of Qendra Multimedia, that “projects like this and cooperation lead towards the democratization of our countries, building bridges of communication, and even reconciliation, because they explore our common history and people’s suffering in the past wars”. Manojlović’s Romeo and Juliet was funded by the Ministry of Culture of the Republic of Serbia. Many officials of the Serbian Government attended its official opening night. Immediately before the opening night, the director said to the daily newspaper Kurir: “The play is not about Serbs and Albanians and relations between Belgrade and Pristina. It is about the possibility of love, the capacity for love that each human has”. Blic reported that the audience learned how to say “I love you” in Albanian (”te dua”).

By offering an overview of what theatres have done and dealt with in the post-war post-Yugoslav space, this text aims to show the ways in which the region has reflected on reconciliation, or at least restoring regional ties, and on the postwar situation and skeletons hidden in the closets. These topic were also discussed at the panel session dedicated to the Use of facts in Artworks, at the Tenth Forum for Transitional Justice organized by the Coalition for RECOM.

Regional Consultations with Artists on the Legacy of the Past, held at the very onset of the RECOM process in 2006, were also dedicated to these topics.

It will be apparent, of course, that many fine stage plays that have also strongly influenced theatre audiences have not been discussed in this text. Oliver Frljić’s Aleksandra Zec, for instance. Or plays that remained unknown to a wider audience, but were nevertheless important and influenced the lives of artists and audiences.

© RECOM.link