25.05.2016.

ICTY exposes the gap between individual criminal justice and the writing of history

“Finally, good news from The Hague!” famously cried the then Serbian prime minister Ivica Dacic at the acquittal on appeal of former Yugoslav army commander Momcilo Perisic by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. For him, and for the government he represented, this counted as vindication of Belgrade’s actions during the war. The fact that Serbia as a state had already been held partly responsible by the International Court of Justice (ICJ) for the very crimes this individual was tried for, was swept under the carpet [IJT-63].

by Joost van Egmond, The International Justice Tribune (IJT)

It’s a familiar sight throughout the former Yugoslavia. Former Kosovan prime minister Ramush Haradinaj was treated to a hero’s welcome on his return to Pristina after acquittal at The Hague [IJT-141]. So was Croatian general Ante Gotovina back home, after successfully appealing a previous conviction. It’s indicative of the scoreboard mentality which often frames the way the ICTY is looked upon in the region. A conviction of ‘your own’ counts as a national loss, acquittal is a win. Never mind the often damning facts that are considered proven in the verdict. It’s about scoring an acquittal. The real self-questioning that would be a step towards acknowledgement of the facts is hardly ever done. “If Gotovina was not responsible for the killing of civilians during Operation Storm – the military push he lead in 1995 – then who was?” asks Mario Mazic, a human rights activist in Croatia. He points out that his country missed a huge opportunity to investigate this question after Gotovina’s release. Many others say the same of their respective countries. But they struggle to be heard.

Can the ICTY achieve reconciliation?

While the ICTY states its work has “helped pave the way for reconciliation” between the former war parties, it is hardly equipped to do so. Pre-occupied as it is with establishing individual criminal responsibility, it tends to zoom in on legal issues that may be very relevant for a trial, but which won’t satisfy victims seeking recognition, nor open the eyes of those who chose to look the other way.

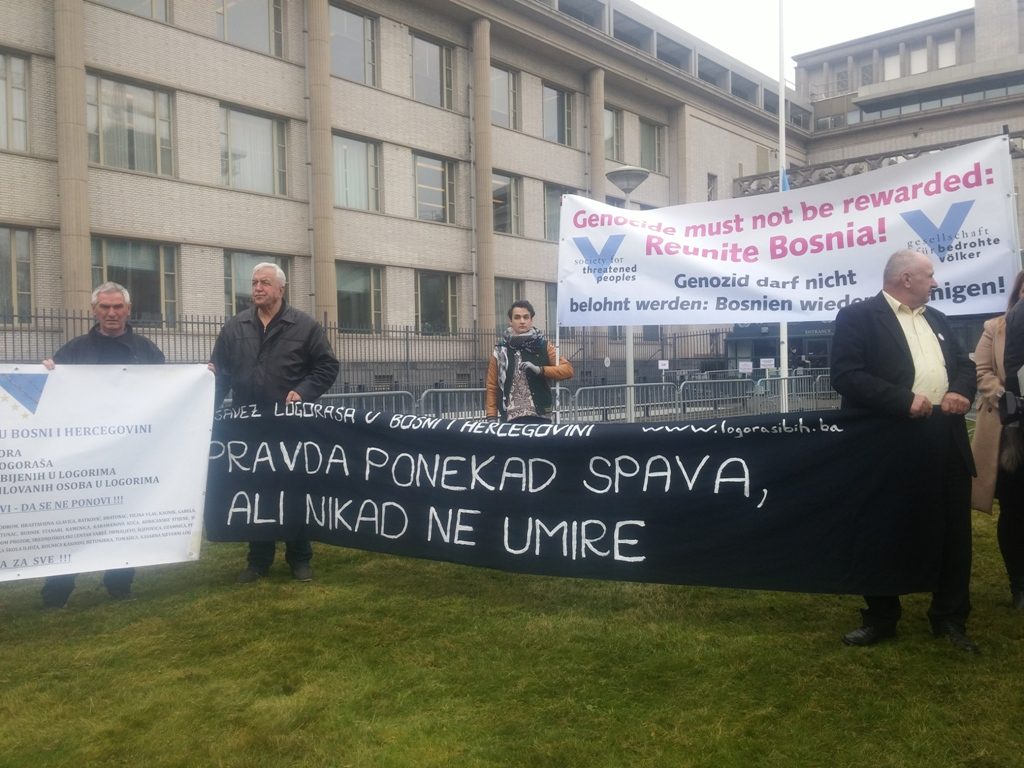

Despite this, in cases that lead to a conviction the tribunal has still led the way in establishing facts that could form building blocks of a historical narrative. But acquittals complicate that effort. An acquittal does not mean a crime has not been committed, but that subtlety is lost on both the suspects supporters and the victims. When Bosnian Serb wartime leader Radovan Karadzic was recently convicted of extermination as a crime against humanity in seven municipalities throughout Bosnia but acquitted of genocide in those places, at least a hundred victims and relatives assembled outside the courthouse labeled this a disgrace [IJT-192]. To them, this was impunity.

“The ICTY deals with individual criminal responsibility, it cannot write history for us, nor should we want it to,” says Mazic. “We need to do that ourselves.” Local activists from across the region have started to do just that by setting up Recom – short for Reconciliation Commission to push for the establishment of an independent commission to investigate what happened during the war. It would steer clear of the legal framing associated with the ICTY and instead focus on establishing the facts of what happened on the ground. “We are based on facts, on what happened to the people in the field. For that legal decisions are not relevant”, says Serbian human rights campaigner Natasa Kandic, a prominent supporter.

The issue of whether what happened in the Bosnian town of Prijedor [IJT-157]could be precisely legally defined as a genocide or not is just one example of the hot divisive debates. The ICTY has established that thousands of non-Serbs were rounded up and held prisoner in terrible conditions and many were killed. An independent commission could help to establish for all parties which individuals were killed where and by whom, providing a historical record that school textbooks could refer to. Research suggests basic knowledge about atrocities during the war is declining rather than growing as a new generation grows up.

Nearly a decade after Recom initiative, an actual commission seems far off

Recom has gathered many supporters: more than 500,000 signatures and even the tentative support of key politicians, such as current Serbian prime minister Aleksandar Vucic. But almost ten years after the launch of the initiative, a commission supported by all former warring countries is yet to be established, and there aren’t many in civil society who expect it to happen soon.

One of the problems is that while recent controversial verdicts at the ICTY have highlighted the need for a non-divisive fact-finding commission, their contentiousness has also reinforced the same divisions that make it hard to support Recom. As long as the scoreboard mentality is entrenched, it is tempting for societies that feel they suffered ‘a loss’ at the ICTY to dig in and focus on their own version of events.

A telling example was a campaign collecting signatures for Recom, which started right after Croatian general Gotovina was convicted in first instance in 2011. It resulted in numerous incidents of intimidation against the campaigners in Croatia, much more so than in other countries. In the end some 20,000 Croatian citizens signed up, spectacularly low compared to Bosnia (120,000) or Serbia (250,000). This is a snapshot of course, and the campaigners themselves mostly attribute it to bad timing. The result may have been very different is the campaign were held right after Gotovina’s acquittal on appeal. As long as the scoreboard mentality is entrenched, it is tempting for societies that feel they suffered ‘a loss’ at the ICTY to dig in and focus on their own version of events.

Reaching out to those with a different narrative of the war therefore remains hard. “Many now say that if the judges at the tribunal can’t agree, it’s up to us”, says Mazic. “And in a way it is, but with a critical, multiperspective view, through dialogue. But I don’t see anything like that happening at the moment.”

–This story is the second in a series of four IJT articles focused on the legacy of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) ahead of the special debate “Coming to a close. Trials and tribulations of the Yugoslavia war-crimes tribunal jointly hosted by the Dutch NIOD Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies and International Justice Tribune which will be held in Amsterdam on 31 May. For more information on the debate and speakers and to register click here.–

(Copyrights information: This article originally appeared in International Justice Tribune, 24 May 2016. Visit their website www.justicetribune.com for more international justice stories or follow IJT on Facebook or Twitter @Justicetribune)