It was 2017 when a grotesque discovery was made at a rudimentary wartime landing strip for aircraft in a village near Bratunac in eastern Bosnia and Herzegovina.

When the concrete was dug up, five bodies were found. One of them was Alija Zukic, who had been among hundreds of Bosniaks and Croats who were held captive in the Vuk Karadzic school building in Bratunac in May 1992.

“My brother Alija was taken out of the [school] hall to an old furniture showroom in Bratunac,” his sister Pasa Suljic told BIRN.

“He was found when the improvised runway in [the village of] Ade was dug up. He had been cemented into the runway. He was found together with four other corpses in bags,” Suljic said.

Her other brother, Hedim Zukic, was also killed.

“As surviving detainees told me, my brother Hedim was killed by his work colleague Milan. He took him out of the school building to weld bars for the prison. He was never brought back to the school,” Suljic said. Her brother’s remains were found more than a decade later in a mass grave in nearby village of Bljecevo.

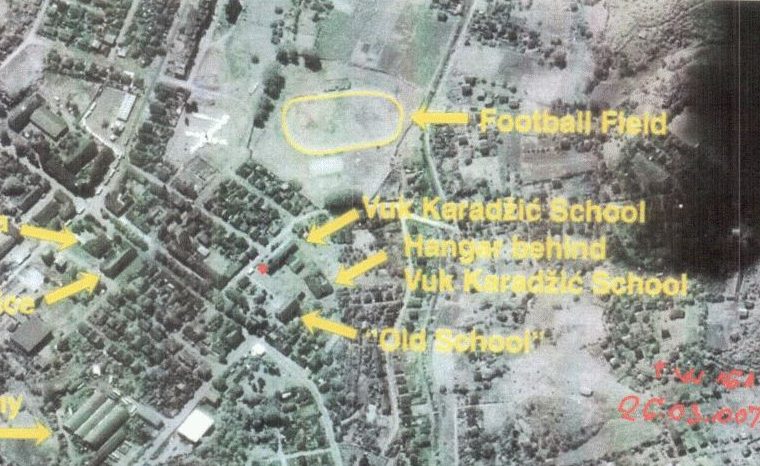

Before the men were separated from the women and children and taken to the Vuk Karadzic school, prisoners of both sexes had been held at a local sports stadium, where the violence and killings began.

“While we were at the stadium in Bratunac, we all saw them kill Miralem Hasanovic, who was known as Rus. My [Serb] work colleagues were at the stadium, carrying ammunition and cartridges. The road from [my] house to the stadium was guarded by soldiers from Serbia. They had Serbian accents and stood in rows on both sides of the street,” Pasa said.

Smiling killers

The Association of Surviving Detainees from Bratunac estimates that around 800 prisoners were held at the Vuk Karadzic school in Bratunac over three days in May 1992. Around 300 of them were killed, the association believes.

Sakib Ahmetovic was arrested in the village of Redjici on May 10, 1992 with his sons Muhamed, who was 13, and Mirzet aged 12. He was taken to the sports stadium, where he was told, as the other prisoners were, that they would be freed in a prisoner exchange.

Instead he was taken from the stadium to the school detention camp.

“It was horribly crowded and hot. Ten people suffocated to death due to panic and the lack of air on the first day. After that, the awful beatings and killings began,” Ahmetovic told BIRN.

“I saw Dzemo Hodzic and imam Mustafa Mujkanovic fall down dead due to the beating. I knew both of them. Those were gruesome murders. Not murders with firearms, but murders caused by beatings,” he said.

He claimed that the first murders were committed by members of a paramilitary group led by the notorious Serbian criminal Zeljko Raznatovic, alias Arkan, who was shot dead in 2000 not long after being indicted by the Hague war crimes tribunal.

After the initial murders, Ahmetovic continued, “local soldiers also began to kill people”.

“Those were our neighbours and acquaintances. They would enter the [school] hall smiling and take people out to be shot. They said: ‘We will kill all of you, slowly; we cannot kill you all in one go, we are enjoying it,’” he recalled.

Three brothers, Ismet, Hasim and Nedzib Husic, were among those brought to the school. Ismet and Nedzib were killed.

“Everyone says that [Nedzib Husic] was killed on the stairs. He did not even make it to the school hall,” said Ismet Husic’s son Adis, who has spoken to surviving detainees about what happened.

“My father was taken from the hall to be shot. They allegedly took him to the Ministry of Internal Affairs for interrogation, after which they killed him and many other Muslims,” he added.

His mother Sadika was also killed after running away to the woods with other neighbours in an attempt to escape.

No murder convictions

Numerous surviving detainees said they have given many statements to investigators over the past 28 years about the murders of the detainees in the school building in Bratunac, but so far not a single person has been convicted under a final verdict.In 2015, the Bosnian state court acquitted Savo Babic, the wartime commander of the military police in Bratunac, of charges of unlawful detention, beatings, forcible disappearances and murders of prisoners at the school. The indictment in the case claimed that around 400 people were held there.More than a decade before the Babic verdict, in 2004, prosecutors in Tuzla Canton opened an investigation into 43 individuals suspected of committing war crimes in the Bratunac area during 1992.“The legal classification of the crime, as specified in the order to conduct an investigation, was genocide. It covered the events associated with murders and deportation of a number of civilians in the broader Bratunac area, including the villages of Hranca and Glogova, as well as the Maljevo and Jezero localities, and taking civilians to a detention camp at the Vuk Karadzic school and to [the town of] Pale or to the Batkovic detention camp, near Bijeljina,” Admir Arnautovic, spokesperson for the Tuzla Cantonal Prosecution, told BIRN.

Stadion u Bratuncu. Foto: Inicijativa za obilježavanje neobilježenih mjesta stradanja

The Tuzla prosecution handed the case over to the state-level court and prosecution, which confirmed that it is still investigating “several individuals” for the crimes committed at the school.

“The cases are being worked on intensively,” Bosnian state prosecution spokesperson Boris Grubesic told BIRN.

In July this year, former Territorial Defence fighter Milan Trisic went on trial for detaining, assaulting and killing Bosniak civilians who were taken from their village and held in captivity in Bratunac in May 1992.

Trisic had been deported to Sarajevo in October 2019 from the United States, where he had previously been prosecuted for lying to the US authorities about his participation in the war.

The court at the Savo Babic trial established that Yugoslav People’s Army troops and Serb Territorial Defence fighters were active in the villages around Bratunac in May 1992.

Survivors also claim to have seen many paramilitaries from Serbia in Bratunac at the time who were involved in detaining non-Serbs.

The War Crimes Prosecutor’s Office in Belgrade declined to reveal whether or not it is conducting any investigation into wartime crimes in Bratunac, “bearing in mind that investigation and pre-investigation processes are not made public”, said Vasilije Seratlic, Serbia’s deputy war crimes prosecutor and spokesperson for the prosecution.

Corpses in garbage containers

Ramiz Salkic, a Bosniak who is now the vice-president of Bosnia’s Serb-dominated Republika Srpska entity, was brought to the school as a prisoner at the age of 17.

“Corpses were in the canal next to the school building and in garbage containers. They had already been killed before we were detained in the school,” Salkic recalled.

Among the victims he saw was his father Hamed, whose dead body lay in the canal for days.

“With that image in my head, I entered the detention camp. I wanted to be the next one to be killed,” Salkic said.

“Around ten detainees suffocated to death in the hall, because we did not have enough air. They took people out of the hall. Those who were taken out mostly did not come back alive. My brother Hamdija was beaten up next to me. They beat him with a radiator pipe. An hour before my arrival in the detention camp, my brother Ahmet had been killed with a metal stick,” Salkic continued.

He was escorted to the school gym, where he used to play and attend classes as a child several years earlier.

“I watched them mistreat people. They shot one of them in both legs, and were asking him to stand up. In the end they shot him in his forehead. I shall never forget the image of a thin stream of blood pouring from his forehead,” he said.

After three days at the school, the prisoners were moved to the Bosnian Serb wartime stronghold of Pale, where Salkic claimed they were also abused.

Three days after that, on May 16, 1992, the survivors of the ordeal were finally allowed to cross over into territory controlled by the Bosniak-led Bosnian Army in the town of Ilijas.

Adnan Krdžalić

This article was was originally published on detektor.ba.