20.04.2016.

Untold Stories of Croatia’s Wartime Forced Evictions

By Sven Milekić, BIRN

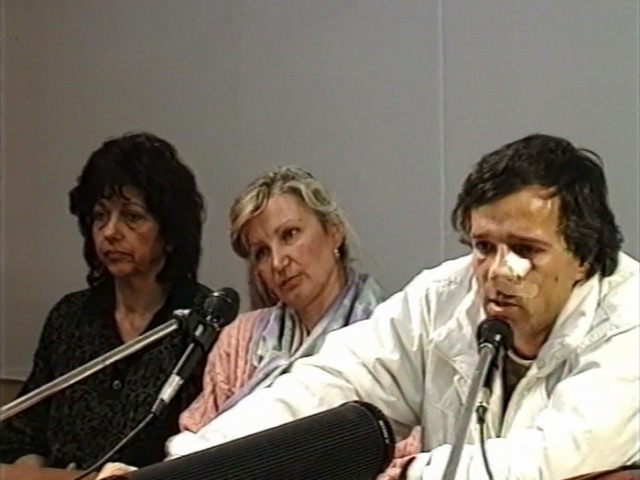

“I can’t even believe that all this happened to me. Really. My mind can’t comprehend it,” 64-year-old Slovenka Marinkovic said as she sat in her cosy apartment in the Croatian coastal city of Split – the home from which she was forcibly evicted during wartime.

“For the purposes of the lawsuit, the doctor asked me to describe how I felt at the moment that this was happening in my apartment. I was already crying just thinking about it. I said to him: I simply put myself in the position that this isn’t happening to me, otherwise I would go insane,” she added.

Marinkovic was one of the many victims of forced, sometimes extremely violent and almost exclusively illegal evictions of Croatian citizens from apartments given to its employees (both officers and civilians) by the former Yugoslav People’s Army, JNA, during the 1990s.

Most of those evicted were women living alone with children or elderly relatives – and most were Serbs.

Under the Yugoslav socialist regime there were limited rights to private property. The JNA owned between 35,000 and 40,000 apartments and houses in Croatia, to which it gave hereditary tenancy rights to its employees.

When the war broke out in 1991, soldiers and armed vigilantes, sometimes aided by the military police, forcedly broke into many of these homes and threw out the occupants, targeting mostly but not exclusively Serbs.

Some of these evictions were carried out on the basis of defence ministry ‘decisions on temporary use’ of apartments, but some were carried out completely illegally, at gunpoint.

Since most of the people involved in carrying out the evictions were either active or reservist soldiers, the police claimed to have no jurisdiction over the issue, leaving everything to the military police, who condoned the majority of them.

The number of people forcibly and illegally kicked out of their homes between 1991 and 1997 remains unknown, but some NGOs dealing with the issue estimate the figure at around 10,000.

Although some of them later returned to their apartments after years of legal struggle, others never got back their property and left Croatia for good.

But most of those who were lucky and persistent enough in their legal campaigns to get back their homes never received any compensation for the property stolen from the apartments – and none of them were compensated for the stress and the health problems that they suffered as a result of being kicked out.

Death threats and armed raids

Slovenka Marinkovic, who was born in the Serbian town of Leskovac, moved to Split in 1972 with her husband, who was a JNA officer. She separated from him in 1987 and he left Croatia with the JNA in 1991 at the beginning of the war, leaving their apartment’s tenancy rights to her.

Her 18-year-old daughter also left Split in 1991, enrolling in college in Belgrade, followed by her younger daughter who also went to Serbia to live with her grandmother after being threatened with rape and murder on the phone several times because her father was a JNA officer.

Marinkovic was under a lot of pressure herself; her phone line was cut off and she was accused by her colleagues at the local pharmacy of “aiding rebel Serbs in [the town of] Knin”.

She said that in 1993 there was one failed attempt by a group of soldiers to take her apartment, which she stopped by getting together with her female neighbours. But later that year, the local Croatian Defence Forces, HOS, unit, which was named after WWII-era fascist commander Rafael Boban, became more active in carrying out illegal forced evictions.

According to Marinkovic and Tonci Majic, a local activist who tried to stop the evictions, the unit was led by their commander Ivan Perkusic, alias ‘Barba’. Rudjer Boskovic Street, near her apartment, was the epicentre of the Rafael Boban unit’s activities, where they evicted dozens of families and where today, a monument to the unit stands.

When Perkusic evicted a mother and her small daughter from an upper floor of Marinkovic’s building, forcing the woman out with a gun to her head, she said his fighters then transformed the apartment into a centre for dealing drugs and illegal gambling, and she realised that he would soon come to her door too.

When Perkusic and his armed associates did knock in February 1994, she refused to open up, but he broke down the door and got in anyway. One of them called the police, and two officers arrived but they couldn’t do anything to help her.

“These poor policemen… I was so mad and so angry, I was arguing with [the soldiers], I was so belligerent and [the policemen said] to me: ‘Please, please, don’t let them kill you – anything can happen,’” Marinkovic said.

Because she was angry, Marinkovic told them that Croatian citizens “will never get a state” if they behaved like this. One of the soldiers went to hit her and Majic came to her defence, getting his nose broken in the process.

Marinkovic and Majic were taken by the military police to the Lora military prison in Split, where Serb civilians were tortured during the war, according to court judgements, but released after a few hours after the intervention of deputy defence minister Goran Dodig.

They tried to get back in to Marinkovic’s apartment, but there were already a lot of soldiers there, stealing her possessions.

“I told the military police that these people are… stealing my things, and asked whether it was normal for them to just watch.And one said to me, do I have receipts for these things? I asked him which ones, and he just said that it all belonged to Croatia,” she recalled, laughing ironically.

Dodig helped them to arrange a meeting with the head of the military police, Mate Lausic, but he refused to help.

“When I told him that the soldier occupying my apartment should be taken out, he said: ‘No, Mrs. Marinkovic, I have no moral right to expel a Croatian soldier from your apartment,’” she said.

She eventually got her apartment back six years later, in 2000, winning a case against the former soldier living there. She also got some compensation for her damaged and stolen possessions as well as a refund for the rent she paid while not living at home.

She also launched a case seeking damages for the mental anguish caused by the whole incident – the first and only evicted person to have done this. Although she was awarded around 10,000 euros at Split’s municipal court, the county and supreme courts ruled against her, saying the incident would not have had a lasting impact on her mental state.

“Horrible, it was horrible,” she said. “What has always bothered me is that they act as if nothing happened here. They suggest that all was well and good; that people were left to live normally, that no one here had a problem.”

‘Suddenly I became invisible’

Slobodanka Postic, a 71-year-old teacher of English, Polish and Russian, used to work as an interpreter at the JNA’s military academy in Zagreb – until 1991, when everyone lost their jobs after the academy was taken over by the Croatian defence ministry.

As well as struggling to find a new job, she saw some of her friends and acquaintances turning their backs on her because of her mixed ethnic background.

“I then realised who my friends were, because a number of people simply ceased to see me; suddenly you become invisible,” Postic said.

In 1992, her child went to live with family friends in the Polish city of Cracow. The following year, Postic visited Cracow with her partner and mother, but as soon as she arrived, she got a message saying that some soldiers had broken into her apartment.

She and her partner went back to Zagreb the next morning, but it was too late.

“We arrived at the apartment during the night; the lock had been changed. We rang the bell and a woman opened it and said that the apartment had been assigned to her,” she said.

She told the woman and some soldiers who were in the apartment that it was hers and that she had no intention of leaving it. A group of seven or eight armed men came and took them inside and started asking questions.

“Because I translated into Russian and Polish, I had a table over the computer [keyboard] with the Russian and Polish alphabets, with all the letters… For them, it was a proof that I had encrypted messages,” she said with a little smile.

Postic said she went to the apartment with a document proving she had the right to the tenancy, but the document was taken from her and the police who came later could not enter the property and subsequently said that they had no jurisdiction over the case.

She went to the defence ministry, where a woman who was working there told her: “I would leave Croatia if I were you.”Then while applying for welfare benefits, as she was a single parent without work and a permanent residence, office clerks said that she had to change her address in order to receive mail, which would cause her to lose the tenancy rights to her apartment after six months.

When she was at the municipal court, filing some documents for her case, one court official said to another: “I’ll come back to you once when I am done with this Chetnik woman.”

Mementoes and books lost forever

A couple of months after Postic was evicted, a neighbour called her to say that people were taking her things out of the apartment. When she arrived, she saw uniformed men loading her possessions onto trucks.

When she asked them where they were taking them, one of them responded: “Madam, you should be killed, not given a reply about where your things are going.” One soldier then threw her child’s pillow down from her first-floor apartment to taunt her, while another young serviceman stuffed his pockets with her Kinder eggs.

Although she was told that most of the things, including a collection of rare dictionaries that she used for her work, had been taken to a military warehouse, they were not there.

“I spent that summer in someone else’s shoes and clothes, going around antique shops hoping to see one of my books, although I didn’t have a penny… Years later, with some new bookshelves, I would still lift my arm to where the encyclopaedia or dictionary [that was taken] used to be,” she said sadly.

Postic had no money to pay for lawyers but she was a member of the Civic Committee for Human Rights NGO, which funded her cases against the defence ministry for taking the decision to give temporary use of her apartment to someone else.

In the end, she won the case against the ministry and finally got her apartment back in 2005 – but she and her daughter lost everything they had there.

“I remember when we got the apartment years later, my child wrote to me from America, where she was studying: ‘Mum, please just don’t sell the apartment until I see it…’ And then I remember that when we were selling it, that we stroked the walls of the apartment with our hands,” she said, almost crying.

A 15-year struggle for justice

Mirjana Jakopec was a Croat married to a Serb JNA officer, Milutin Jovicevic. Working as a bank clerk in the northern town of Varazdin, she got tenancy of a JNA apartment in the 1960s, which she then gave up so that both of them could get a place together in Zagreb.

Jakopec, who is now 71, divorced Jovicevic in 1990, the year he was moved with the JNA from Zagreb to Belgrade.

As a Croat who was married to a JNA officer, she and her son Jovica were harassed from the early 1990s onwards in Zagreb; one time, ten armed men came to her door in an attempt to intimidate her into leaving.

She claims that the defence ministry never sent any documents saying that her right to the tenancy was being challenged. But when her son came home one day the end of August 1992, he found that the lock had been changed and that someone else – a war veteran called Jure Mrkonja – was in the apartment.

When she asked Mrkonja to leave, he refused.

“He said: ‘I’ve got nothing to do with you. I’ve got a [tenancy] decision [from the defence ministry], it’s mine,’ he said. I told him: ‘But it is not yours; they can give away the whole city… but this is mine,’” she said.

Mrkonja gave her a week to take her things out of the apartment. She went to the police, who said they did not have any jurisdiction over soldiers.

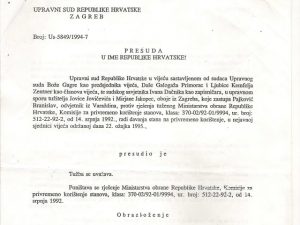

Jakopec later discovered that her right to the tenancy had been waived a month earlier, but she explained that the housing committee at the defence ministry had made two illegal moves while doing so.

First it produced an internal report wrongly saying she was not living there anymore and so the apartment could be given to someone else because they were not the legal tenants. Then it gave a licence for temporary use to Mrkonja, which was later proven to be unconstitutional.

Jakopec spent around 25,000 euros on lawyers, who were able to win her a case at the administrative court in March 1995, which rescinded the decision to revoke the tenancy the previous year.

But the decision was not enforced, and the case then dragged on through the courts for 12 more years.

Finally, one day in December 2005, during one of her occasional walks around the building in which the apartment is located, she saw that there were no lights on. She called her neighbour to ask if there was anybody inside.

“He said to that Mrkonja left and moved out of the apartment,” she said.

“The lawyer came with me and rang the bell. When there was no reply, he said: ‘Get into the house.’”

Activist Semina Loncar called a locksmith, telling him that Jakopec had lost the key, while another activist, Zoran Pusic, brought a sofa and two chairs, so it looked like she was already living there. Jakopec took possession immediately and Mrkonja never returned.

Jakopec finally won her case at the municipal court in 2007, ending her 15-year-long struggle to officially restore her tenancy of the apartment, although she had to repay an additional 17,000 euros to the state, plus additional costs for damage to the apartment caused by Mrkonja. Her garage and car, which were both confiscated, were never returned.

“You know, when my lawyer called and said ‘we won the case’, I said, ‘I do not believe you; that is impossible,’” she recalled.

“After all the manipulations and the attempts to defeat me, they didn’t succeed. I was stronger,” she added with a smile.

“I am one of the very few who managed to get back into their apartment, but only thanks to the fact that I was persistent.”